Communities across Florida are already grappling with aging septic tanks, which leak into groundwater and are considered a leading cause of toxic algae blooms. As sea level rise is expected to worsen that situation, the state and cities are beginning to tackle the expensive task of converting septic systems to sewer or newer septic technologies.

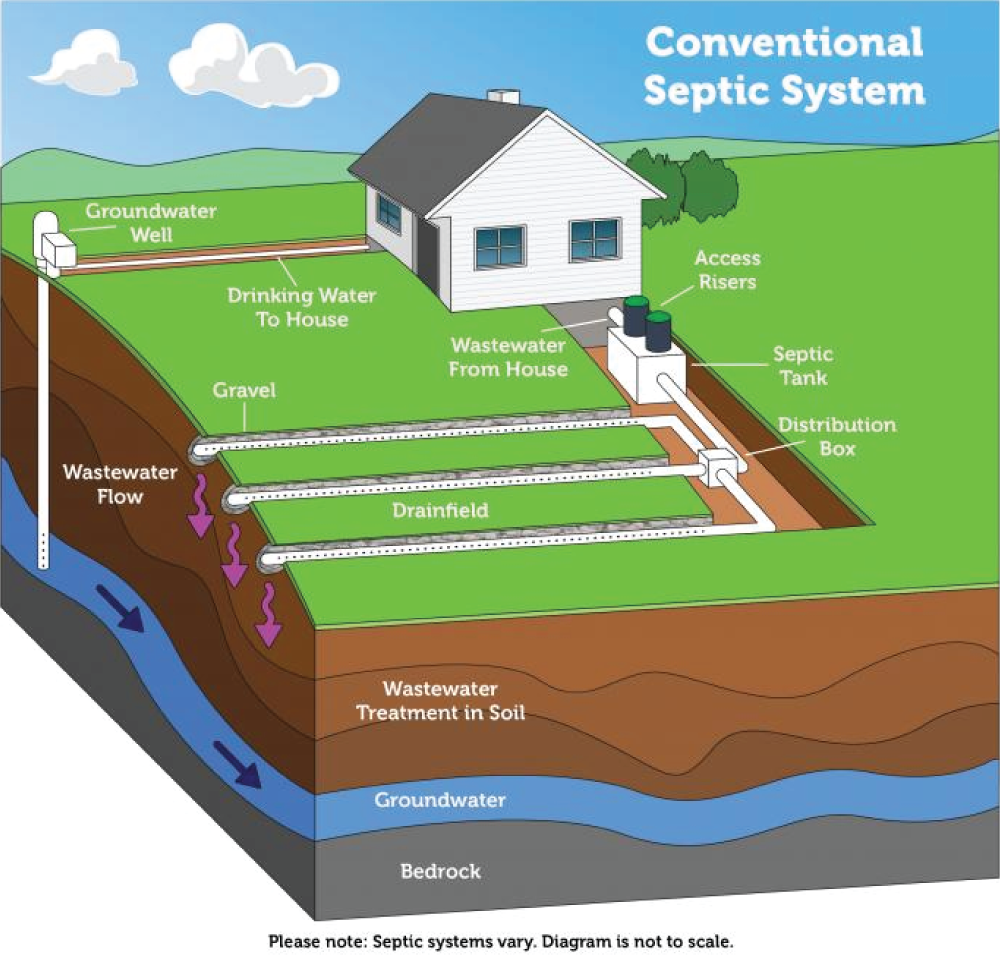

It’s no small challenge. Floridians are estimated to be using 2.6 million septic systems, most of them the conventional variety with two parts: a tank in the ground close to the home and a “drainfield.”

An algae sample is collected in April 2019 from a bloom at Buffalo Bluff near Palatka.

Credit: Tim Ho/St. Johns Riverkeeper

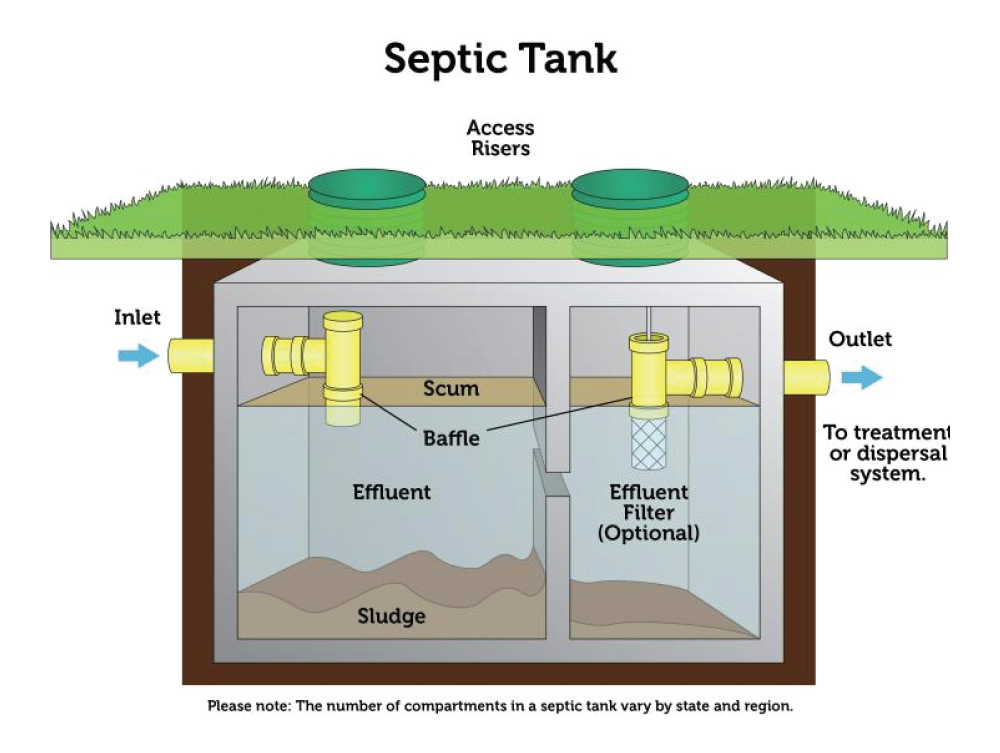

A quick septic 101: When someone flushes a toilet or rinses off a plate, the wastewater is pumped into the tank, where “solids” settle to the bottom, forming “sewage sludge,” while oil and grease float to the top, forming “scum.” When septic systems get pumped, it’s to remove built-up sludge and residual scum.

Bacteria inside the tank perform the first stage of treatment by breaking down waste. The resulting liquid, called “effluent,” then flows out of the tank and into the drainfield, most often a patch of soil. This serves to filter out some pollutants and contaminants before the effluent reaches groundwater.

Mary Lusk, an assistant professor in the University of Florida Soil and Water Sciences Department, said this plain old technology is generally effective when it comes to public health protection.

“They do a very good job of removing bacteria and viruses and any other pathogenic organisms as that wastewater interacts with the soil,” she explained. “Our problem in Florida is that the basic conventional system was never designed to remove nitrogen, and nitrogen is ever present in the human waste stream.”

Nitrogen, a colorless gas, is the most common element in the earth’s atmosphere and is present in all living matter. But when it gets into our water, it’s also a leading cause of harmful algal blooms.

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences says the blooms can sometimes be deadly.

And in Florida, where the soil isn’t the best at filtering, by the time the post-septic wastewater reaches ground water, it’s still full of what’s called nitrate-nitrogen — the stuff of algae’s dreams.

Lusk said, “It’s a nutrient that they’re able to use, and once they have that they’re just happy to gobble it up, and it enables them to thrive and reproduce and get to that algal bloom level.”

Other sources of nitrogen in Florida’s water include fertilizer, livestock waste, polluted rain and wastewater treatment facilities. But septic tanks remain the main culprit of the state’s algae woes, even as nitrogen fertilizer production has risen sharply in recent years, said Brian Lapointe, a professor at Florida Atlantic University.

A recent Florida Department of Environmental Protection study of Wakulla Springs, just south of Tallahassee, found 51% of the nitrogen in that system was coming from septic tanks. A similar study at Silver Springs near Ocala found septics were behind about 40% of the nitrogen in that system.

Lapointe said researchers know the nitrogen is coming from septic tanks because they’re finding similarly high levels of fecal bacteria, sucralose and acetaminophen — “human tracers.”

“In the summertime, when you have seasonally high water tables, you really can’t even meet the minimum state criteria for the separation.”

– Brian Lapointe, a professor at Florida Atlantic University

“There are not other sources in those study areas for those human tracers,” Lapointe said.

He said, compared with septic tanks in other states, Florida’s are problematic for three reasons: the state’s high groundwater level, relatively low levels of organic matter (i.e. bacteria) in the soil and the fact that the soil is so porous and sandy.

“Unfortunately, in Florida, the conditions for proper functioning of septic systems are rarely met in these low-lying coastal areas,” he said.

Lapointe’s 1990 study in the Florida Keys found the levels of algae-feeding compounds to be 400 times higher in the groundwater below septic systems compared with groundwater in an area with no septic systems. Not only that, but the amount of nitrogen peaked during the summer rainy season.

Groundwater in Florida rises and falls depending on the weather. That’s why the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommends 3 to 4 feet of separation between the bottom of a septic system’s drainfield and the “seasonally high water table” — the highest groundwater is expected to get during the summer.

The state of Florida requires just 2 feet of separation.

“In the summertime, when you have seasonally high water tables, you really can’t even meet the minimum state criteria for the separation,” said Lapointe.

In Lee County, he recently found more than 90% of the drainfields of aging septic systems in North Fort Myers were less than 2 feet above the high water table.

“What this means is… you’re not getting adequate treatment of that septic tank effluent,” he said.

And as oceans rise all over the world, it appears the worst could be yet to come.

‘Between hell and high water’

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers anticipates a global mean sea level rise of between 8 inches and 6.6 feet by the year 2100. As seas rise, they encroach into groundwater, increasing its level.

Climate change is also causing rain and flooding to become more frequent and more severe.

Warmer air, one effect of climate change, can hold more moisture. That means when it rains, it rains more. Warmer ocean water, another climate change symptom, makes hurricanes larger and more intense.

Lapointe said this inundation of water from above and below is putting Florida “between hell and high water.”

“These groundwater levels are coming up to the point, in many areas, where they basically flood the drainfield of the system and actually can come right up to the ground surface during storm events such as Hurricane Irma, where you then have a case of overland flow of very poorly treated wastewater,” he said.

As The Florida Times-Union reported, floodwaters after Hurricane Irma carried pollution from many sources, including septic tanks, into the St. Johns River.

Sewage overflows can trigger outbreaks of dangerous waterborne diseases, they can kill fish, and, when sewage flows into homes and businesses, expensive repairs and decontamination are needed to make the buildings safe.

A 2016 investigation by Climate Central found record rainstorms across the U.S. caused millions of gallons of untreated sewage to spill into streets and waterways.

What’s being done?

When Florida’s annual legislative session ended in May, environmentalists saw the new laws as a mixed bag.

Many of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ environmental priorities made it into the state budget, including $682 million for Everglades and water quality restoration projects — even more than the governor had requested.

On June 20, DeSantis signed a bill establishing the Florida Red Tide Mitigation and Technology Development Initiative. It outlines a partnership between the state and the Mote Marine Laboratory to develop technologies and strategies for controlling red tide — another toxic algae that feeds on septic runoff.

“Innovative technologies will play a vital role in our continued efforts to address water quality issues facing our state,” the governor said.

But many proposals to address environmental issues failed, including one by the Florida Republican Party Chairman, Rep. Joe Gruters, that would have required inspections of septic systems at least every five years and for the Department of Health to develop minimum standards and requirements for pumping out and repairing failing systems. The legislation also would have required a statewide septic system inventory by 2021.

“The good news is that I think it was a learning process for many of the legislators about the complexity of the issue,” Lapointe said. “And there’s more money that’s been appropriated this year to help those local governments move ahead on their own.”

A collective $4.2 million was passed for eight local efforts to connect septic tanks to sewers or retrofit them with new technology:

- Nassau County: American Beach Well and Septic Tank Phase Out ($400,000)

- St. Augustine: West Augustine Septic to Sewer, W. 5th St. ($350,000)

- South Daytona Septic to Sewer Conversion Project ($400,000)

- Brevard County Septic to Sewer Conversion for 1,019 Homes ($500,000)

- Indian River County: North Sebastian Septic to Sewer Phase II ($500,000)

- Lake Clarke Shores Septic Conversion Project ($300,000)

- Pinellas County: Lofty Pines Septic to Sewer ($500,000)

- Naples Bay Red Tide/Septic Tank Mitigation Project ($1,200,000)

In Jacksonville, public utility company JEA has been partnering with the city on its own $45 million septic tank phase-out without the state’s help.

JEA prioritized 35 neighborhoods with about 22,000 septic tanks. The first three neighborhoods targeted are the Northside’s Biltmore, Beverly Hills and Christobel.

“A lot of this work involves reaching out to the community because you have to have community buy-in as to how this program is going to work,” said outgoing Jacksonville Chief Administrative Officer Sam Mousa. He and JEA Chief Operating Officer Melissa Dykes have been chairing the committee leading the phase-outs.

“They understand that if the sewer lines go in, they must hook up,” Mousa said. “And if they don’t hook up, they will be charged a minimum charge each month, regardless as to whether they hook up or not.” No work can start until 70% of property owners agree, he said.

In the Biltmore “C” area, JEA plans to eliminate 258 septic tanks at a cost of $10.4 million.

In Beverly Hills, the utility expects to spend about $17.4 million to get rid of 749 septic tanks. Construction is expected to begin in the summer of 2020.

Mousa said neighborhood participation has not yet been solicited in Christobel.

“With the cost of construction these days, which is becoming more and more expensive because the economy’s blowing up,” he said, “we think we’ll be able to do Christobel, but we’ll have a much better handle on actual real-time costs when we get Biltmore ‘C’ in. Then we can decide how far we should go with Cristobel.”

There are an estimated 65,000 septic tanks in Duval County. JEA thinks it would cost more than $2.1 billion to offer all their homeowners sewer service.

“To connect to water and wastewater infrastructure, including laying the infrastructure in the ground, costs between $35,000 and $40,000 for each connection,” Dykes said during a February JEA board meeting.

That’s why JEA is looking for a cheaper alternative. Earlier this year the utility issued a request for proposals with the goal of reducing costs and the time required to phase out the city’s septic tanks.

The city also recently announced it would be piloting a technology called Microbe-Lift that uses bacteria to remove nitrogen from water bodies. In one 2015 test, it helped by as much as 60%, the company Ecological Labs says. The Jacksonville pilot will cost $300,000.

The challenge is the same across the state. While there are plenty of more environmentally friendly septic alternatives, none of them are inexpensive.

However, cost-sharing programs can help lighten the load. Jacksonville has a septic grant program for business owners in the Northwest Jacksonville Economic Development Fund area. The St. Johns River Water Management District offers programs for local governments, agricultural producers and others. The EPA has several programs too, including septic upgrade assistance for homeowners.

“If we want to mitigate these harmful algal blooms that we’re seeing increasing, then we really need to begin to chip away at the major nitrogen sources that are feeding them,” said Lapointe.

Copyright 2019 ADAPT